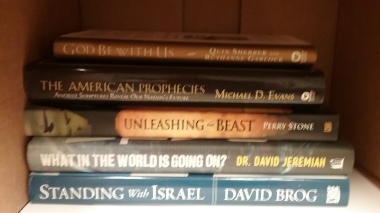

Recently, I came upon a whole kit ‘n caboodle of purportedly Christian books about end-times prophecy and Israel. One of the book titles—Standing With Israel—encapsulates a common theological-doctrinal position that treats modern Israel as though it were integral in future redemptive events. I do not sympathize with that line of thinking, but I am no longer incredulous when I encounter it. I find it likely to be a politically based (whether subconscious or overt) position—secular in import.

Also recently, I happened on a well-written document that treats modern geopolitics in a theological context. The piece comes across as a sort of manifesto. Its logic is circumspect and rational; its ethic, kind and just. I found myself reading along with a great deal of appreciation . . . to a point. I will share portions of this document below, showing in boldface type some statements I sincerely wish I had written myself, and others to which I’ll take exception.

The reign of God

The context of Jesus’ ministry was the Roman imperial rule over Palestine. It was an urgent situation for the Jews of that place and time. What was at stake was not only their economic survival and physical health, but the values that underlay their communal existence as set out in the Torah and reinforced by the prophets: care for the most needy and vulnerable, economic and social equality and compassion for all living things (Exodus 20, Leviticus 25, Deuteronomy 5, Micah 6). Affirming that the rule and reign of God was at hand (Mark 1:15), Jesus declared God’s renewed demands for justice, such as the cancellation of debts and mutual cooperation. In addition, he issued a radical new command—to love one’s enemies—an actionable ethic capable of transforming the hearts of the other as well as directing one’s own heart and actions toward justice and loving kindness [sic] (Matthew 5:43-48, Luke 6:27-31). He renewed God’s demand that people not serve Mammon through the expropriation of others’ resources and taking of land, and enjoined them to not trust in security maintained by violence (Matthew 26:52). Jesus’ proclamation of God’s reign is radically life affirming. It is for this that we pray and to which we devote our work and this document. But misreadings of the Gospel have led to the horrors of the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, the conquest of the Americas and the wars, genocides and ethnic cleansings of our modern age. In our own country’s history, biblical texts have been used to support beliefs and actions that elevate one people or one race over another. The Bible has been used to justify the destruction of people of the First Nations, slavery, and institutionalized discrimination against numerous groups based on their racial, gender or ethnic identity. In our day, misunderstandings or erroneous readings of the Scriptures have led to theologies that continue to support conquest and oppression. We turn to a consideration of two issues in theology that bear particular relevance to our response to this urgent situation for our faith, our churches and our nation.

The above establishes a fine foundation in terms of historical context and scripture. I especially appreciate the phrasing “rule and reign of God,” the emphasis on ethical, justice-seeking living in which an acted-out love of others is paramount. To describe Jesus’ “proclamation of God’s reign” as “radically life affirming” is not only appealing; it’s revealing—and, I would add, accurate.

It appears wise to have introduced some of the horrors of history here, yet those very appeals may prove to obscure present realities even as they spotlight some from the past. In other words, knowing about the Crusades and the Nazi Holocaust is deeply important, but focus on such historical extremes as past Jewish genocide in Europe may lead to a present pendulum-swing of consciousness in which Christian faith is thought to be expressed by (1) acceptance of Islam on some level or (2) support of the state of Israel today. In no way do I seek to minimize the realities or ramifications of the Crusades or the Holocaust. Still, as much as it is true that “misunderstandings . . . of the Scriptures” have resulted in philosophies and practices of “conquest and oppression,” support of the Israel state today above any other political entity is anything but a foregone conclusion–and is in any event not directly related to ancient Jewish history, its ketuvim (writings), or its nevi’im (prophets/prophecies).

Christian Zionism

Christian Zionism is a movement in Christian theology that has enjoyed popular support in churches. Appearing in a number of forms, it has had an impact on Christian thinking and theology in modern history, even influencing the actions of governments, including our own. Traditional Christian Zionists maintain that the Jewish possession of the Holy Land presages the End Times. The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 was, in their view, the next step toward the fulfillment of God’s plan as is foretold in the Bible. Indeed, belief in the Jewish people’s special tie to the land can be found across the Christian theological spectrum. Many Roman Catholic and Protestant theologians today grant the Jewish people a special claim to the land linked to their election by God for a special role in history.

The establishment of the State of Israel continues to take on a clearly biblical cast; the emergence of the Jews from the horror of the Nazi era into the miracle of the Jewish state evokes the triumphalism of the exodus and the conquest as depicted in the Old Testament narrative. In this view, Israel’s military victories in 1967 and 1973 were further confirmation of a divine hand at work in history.

We maintain that it is theologically, historically and politically incorrect to equate biblical Israel with the modern State of Israel. We reject Christian Zionism in all its forms because it supplants God’s gracious presence in all the world with a territorial theology and with the promise of land to one particular people, a promise that leads inevitably to the oppression and even dispossession of other peoples. We reject the idea that God’s ongoing covenantal faithfulness to the Jewish people (Romans 11:28-29) can be legitimately bound up with such claims.

We believe that a role for the Jewish people will include their participation with all peoples in a new order of justice, equality and universal peace that Jesus calls the realm of God. In embracing this vision, we are not taking the land away from the Jews or in any way denying to the Jewish people their fundamental right to live in peace and security and to express themselves as a people and a culture. Nor are we challenging the reality of the Jewish people’s special tie to the land in their own experience and in the view of many Jewish as well as Christian theologians. Rather, we believe, in the words of the Kairos Palestine document, that the land “has a universal mission. In this universality, the meaning of the promises, of the land, of the election, of the people of God open up to include all of humanity, starting from all the peoples of this land.” (2.3)”

We are aware that in rejecting a theology that gives the Jewish people a primary right to the Holy Land, we risk being charged with reviving the Christian doctrine known as replacement theology (also known as supersessionism). This doctrine claims that the Church has taken the place of Israel in God’s purposes, and that the Jews have been condemned to suffering as punishment for rejecting the Gospel. Replacement theology denigrates the Jewish people and Judaism itself.

I envy some of the phrasing above; it seems nearly perfect, for instance, to “reject Christian Zionism . . . because it supplants God’s gracious presence in all the world with a territorial theology.” It appears wise, if unnecessary, to mention the “horror of the Nazi era.” (It should go without saying that no one intends to perpetuate such human horrors in presenting a theological viewpoint.) To paint the establishment of the current State of Israel as having taken on a “biblical cast” is insightful. The point, of course, is that the realities of the middle of the 20th century are not authentically related to biblical history.

I want to be cautious here. (I want to be, but I’m not sure how cautious this will seem.) I simply must go further, rejecting the notion that God has an “ongoing covenantal faithfulness” to the Jewish people per se. If one extends the definition “Jewish people” to include “those believers among the New Israel who accept the one God, history with the ancient Israel, and Jesus of Nazareth as Messiah,” then a covenantal faithfulness to those people is clearly seen. Otherwise, it is my understanding that prophecies related to Israel, although often replete with multiple meanings, find their ultimate fulfillment in God’s work through Jesus. I can believe, along with the framers of this document, that “a role for the Jewish people will include their participation with all peoples in a new [Kingdom] order . . . ,” but that role is for individual Jews who continue to follow through with their belief, not for Jews as a people group.

I do not suspect that Israel’s land has any future significance in the redemptive sphere. (If it does, it will not be because of geopolitics or today’s Jewish people.) I do believe that the Kairos people have appropriately emphasized the universality of God’s invitation: it is an invitation no longer especially focused on one group or human nation.

Christians have rightly wished to distance themselves from this destructive and divisive doctrine. One way in which some Christians have most recently attempted to repudiate replacement theology is to point to the return to the land as evidence of God’s enduring love for the Jewish people. We repudiate the anti-Semitic legacy of the church’s past and the theology that undergirds it. Our core Christian belief is that God’s promise in the Gospel is a promise to all nations. This means that God’s kingdom work in Christ is a promise to everyone regardless of race or nationality. We believe that the Church has found in Christ a fulfillment of all that God promised in Abraham, and that both Jews and Gentiles have been invited equally into this promise of a world renewed in love and compassion. The Church does not replace Israel. Jews continue to have a place in God’s plan for the world. In Christ, all nations can be blessed (Genesis 18:18, 22:18; Galatians 3:8). In these times of growing international tensions and cultural mistrust, this is a significant promise. Theologies that privilege one nation with political entitlements to the exclusion of others miss a central tenet of the Gospel and increase the risks for conflict and violence.

I don’t claim to know all the ins and outs of supersessionism or what is termed “replacement theology.” Nor do I really comprehend the ramifications of one theological stance over another in “conflict and violence” terms. I can only say that my own views, which could be aptly labeled supersessionist or replacement-oriented, are not intended to denigrate Judaism or Jewish people. Rather, I hold that all people, no matter the nationality, ethnicity, or belief system, are of equal value to God. Obviously, ancient Israelites (and “Jews”—a term that came to be used later) had a special significance in redemptive history, but I place emphasis on the chronology. That special place was, but it is no more. No specific (or broadly dispersed) ethnic group has any special place at this juncture. Not Aborignal or Austrian, not Irish or Idumean, not Sioux or Syrian, not Tibetan, not Jewish, or any other. Replacement theology (mine, at least) does not downplay the historical suffering of Jewish people; it certainly invokes no special suffering for today’s Jews because of the role some historical Jews played in Jesus’ crucifixion. My replacement theology does not denigrate the Jewish people at all. It merely places them in perspective.

All the Kairos document material above is excerpted from http://kairosusa.org/study-guide/. Bold typeface in the excerpts above represents my highlights and emphases, not necessarily those of Kairos.

My overall goal here is to further the understanding of the OT Kingdom of Israel as a backdrop—toward grasping the new iteration, the new inbreaking of the Kingdom at the time of John the Prophet Immerser and Jesus the Messiah. In the next post, I will enumerate and expand on some of my own beliefs about Israel past, Israel present, and Israel future.

To be continued . . .

Thanks, Brian.

Sounds as if we are in the same boat, re: ethnic Israel. Look forward to your next posting

bob

LikeLiked by 1 person

Visited their site and downloaded the material for viewing later today, DV

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your energy inspires me, bro. It struck me me as a classy, cohesive document. I zeroed in on certain pieces, and you may find other stuff. Would be interested to hear your impressions — but don’t feel obligated with all your reading-list things to do!

LikeLike

Roger that, Brian. I have followed the labors and writings of Miko Peled since his publication of “The General’s Son” as well as the works of Stephen Sizer, an Anglican Curate, formerly a staff member with Campus Crusade. Enlightening.

LikeLike

I looked up Miko Peled, and even a few paragraphs reveal him to be someone the world ought to listen to.

LikeLike

For certain, along with the works of Ilan Pappe and Stephen Sizer.

LikeLike

[…] my last post, I shared some thoughts on Israel and Zionism, taking an extract from Kairos USA material as a […]

LikeLike